The Forgotten First Tattooers of Vancouver: Indigenous Ink

Tattooing in Vancouver didn’t start with sailors, bikers, or old-school tattoo parlors. Vancouver’s first tattoo artists were Indigenous peoples, who had been practicing tattooing for generations before white settlers ever arrived. Tattooing was deeply woven into the culture, identity, and traditions of the people who have called this land home for thousands of years.

But if you try to dig up the history of Indigenous tattooing in Vancouver, especially among the Squamish, Musqueam, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations, you won’t find much. That’s not because it didn’t exist—it’s because it was erased.

The Potlatch Ban: When Culture Was Made Illegal

In 1885, the Canadian government banned the potlatch, the most important ceremony among many Indigenous cultures on the West Coast. Potlatches weren’t just celebrations—they were where history was passed down, social status was recognized, and cultural traditions were reinforced.

Tattooing in Vancouver’s Indigenous communities was often part of these ceremonies. The Potlatch Ban didn’t just make the gathering illegal—it helped erase the record of Indigenous tattooing in Vancouver and beyond. With the ceremony outlawed and cultural practices forced underground, much of this knowledge was lost.

But we do have documentation of traditional Indigenous tattooing in British Columbia, most notably among the Haida of Haida Gwaii. Their tattooing practices give us a glimpse into what may have once been common among other Coast Salish tattoo traditions, including those of the Indigenous peoples whose land became what we now call Vancouver.

Haida Tattoos: A Tradition of Identity and Status

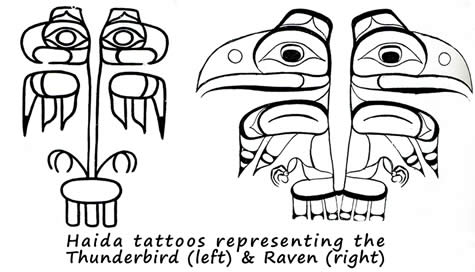

The Haida people are widely recognized as some of the most accomplished Indigenous artists in North America. Their totem poles, canoes, and longhouses are world-famous, covered in intricate symbols and family crests that tell the stories of their people.

Tattooing was an extension of this same artistic and cultural identity. Their skin became a living canvas, marking their lineage, personal achievements, and spiritual connections.

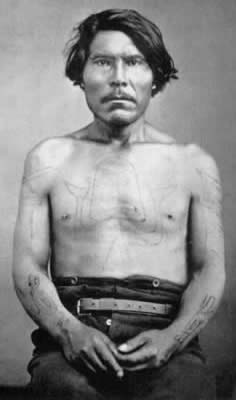

In the late 19th century, a man named James G. Swan became one of the only white scholars to document Indigenous tattooing in the Pacific Northwest. In 1878, he published “Tattoo Marks of the Haida,” detailing how Haida tattoos functioned as heraldic symbols, much like the carvings on totem poles and house posts.

Where Were Haida Tattoos Placed?

Swan recorded the placement of Haida tattoos, which varied by gender:

• Men’s tattoos were commonly placed:

• Between the shoulders, just below the back of the neck

• On the chest

• On the front of both thighs

• On the lower legs, just below the knees

• Women’s tattoos were more visible, often placed:

• On the chest

• On both shoulders

• On both forearms, extending over the back of the hands to the knuckles

• On both legs, below the knees to the ankles

• Some also had facial tattoos, usually in the form of simple dots or lines

For Haida women, tattoos on the hands and arms were especially significant, displaying their family crests and showing whether they belonged to the Bear, Beaver, Wolf, or Eagle clans. These tattoos weren’t just decorative—they were permanent markers of identity and status.

Haida man with wolf spirit tattooed on back.

The Process: How Haida Tattoos Were Made

Tattooing in Vancouver’s Indigenous communities—just like among the Haida—was never just a casual decision. It was painful, slow, and deeply significant. Only a few individuals in the community had the skill to tattoo correctly, and they were highly respected.

One such tattooist, a young Haida chief named Geneskelos, explained the tattooing process:

1. Drawing the Design → The tattoo was first drawn on the skin using dark pigment.

2. Needle Puncture → The artist used a bone or ivory tool with multiple needles tied to it to prick the design into the skin.

3. Pigment Rubbing → Once the skin was punctured, additional pigment was rubbed into the wounds to darken the tattoo.

The tattooing tools were simple but effective:

• A flat strip of ivory or bone was used as a handle.

• Five or six needles were tied to the strip, extending just enough to puncture the skin without cutting too deeply.

Even with pain-deadening substances, the process was brutal—some people were sick for days afterward. Because of this, Haida tattoos were often done in stages, allowing the person to heal before continuing.

Clockwise from top left- 5 cedar batons, carved cedar brushes, a stone dish for pigment, a lump of magnetite (pigment).

The Meaning Behind Haida Tattoos

Unlike modern Vancouver tattoo culture, where tattoos can be purely aesthetic, Haida tattoos always carried deep cultural significance.

• Crest Tattoos → Displayed ancestral lineage and tribal identity.

• Achievement Tattoos → Some tattoos marked significant life events or acts of bravery.

• Spiritual Tattoos → Certain designs were believed to offer protection or supernatural power.

Tattoos weren’t just about personal expression—they were a permanent record of community history.

Why We Don’t Have More Records of Indigenous Tattooing in Vancouver

The Haida weren’t the only Indigenous group tattooing in British Columbia. The Squamish, Musqueam, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations almost certainly had their own tattooing traditions. So why don’t we have more records? Because much of it was erased by colonialism.

The Potlatch Ban and other government policies disrupted the passing down of knowledge. With tattooing ceremonies outlawed and Indigenous communities forcibly assimilated, entire cultural traditions were lost—or pushed so far underground that they weren’t recorded the way Haida tattooing was.

But Indigenous tattooing in Vancouver is making a comeback.

Indigenous Tattooing is Being Revived in Vancouver

After over a century of suppression, Indigenous tattooing is seeing a resurgence across British Columbia. Artists are reclaiming their ancestors’ traditions, using traditional hand-poking and skin-stitching techniques to bring back what was nearly lost.

One of the best ways to understand this revival is through the documentary “This Ink Runs Deep.” The short film explores the revival of Indigenous tattooing across Canada, highlighting six artists who are bringing back their ancestors’ methods and meanings. Originally commissioned by CBC Arts, the film premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) in 2019 and has won multiple awards.

Watch “This Ink Runs Deep”

“Ink marks paths through skin like rivers across the land.” Indigenous tattooing, like the waterways and landscapes of traditional territories, can never truly be erased.

👉 Watch the full film on the CBC Arts YouTube channel:

Indigenous Tattoos Came First in Vancouver

Vancouver’s tattoo history doesn’t start with white settlers or Western-style tattoo shops—it starts with Indigenous peoples, who were tattooing long before colonization.

While records of Squamish, Musqueam, and Tsleil-Waututh tattoos are scarce, the Haida tradition gives us a glimpse into what tattooing may have looked like in Vancouver before colonial interference.

Tattooing in Vancouver has always been a sign of identity, achievement, and spiritual connection—and today, Indigenous artists are working hard to reclaim what was stolen and revive what was nearly lost.

Much of the historical information on Haida tattooing in this post is sourced from Tom Lockhart’s Vanishing Tattoo archive. For more, visit: Vanishing Tattoo – Haida Tattoos. See also tattoo anthropologist Lars Krutak’s article “CREST TATTOOS OF THE TLINGIT & HAIDA OF THE NORTHWEST COAST“

For more on the potlach ban-and plenty of things I wasn’t taught in school-I highly recommend reading 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act by Bob Joseph. It breaks down the lasting effects of colonial policies in Canada and why they still matter today.